Nenana

Written By Maaruk, Warren Jones

Photos by Jackie Cleveland

Why We Went

In this series of stories, we are highlighting people and programs in Indigenous communities that have been funded and supported by Alaska Venture Fund. We traveled to engage with these communities, to work and talk and laugh alongside them, and to highlight the work that they are doing, work that strengthens Indigenous cultures and contributes to nation building.

The Place

Nenana sits in the Westernmost part of the Tanana territory at the confluence of the Nenana and Tanana Rivers. In the Dene language, Toghotthele, the old name for the place, means “mountain that parallels the river.” The area has been used seasonally by the Tanana people for potlatch and summer fishing for 12,000 years.

Getting There

My companion on this trip, the photographer Jacqueline Cleveland, starts her journey in the village of Quinhagak, Alaska, a village of about 800 people on the Bering Sea, 420 miles east of Anchorage. From there, she takes a small plane to a Bethel to catch an actual jet to Anchorage, where we meet up. From Anchorage, we fly to Fairbanks and rent the car that I will drive to Nenana. Uncertain exactly where we will stay or what we will eat, we stop at the grocery store to stock up on snacks and fruits. We also get fresh fruit to give to our hosts. Jacki brought “dry fish” from home–dried and smoked salmon. I was happy to drive the highway there, and Jacki was content to ride. The highway eventually turns to a dirt road that follows the river, and soon, the culture camp comes into view.

The Camp

The camp sits in a clearing along the mighty Tanana River with two screened cabins, a steam bath, a smokehouse, and an outhouse. Cutting tables, fish racks, and a small farm plot area nestle between endless woods and a broad glacial river. Bright blue skies and white clouds contrast with the silty river and the hungry greenscape of summer. The July air is hot and still. Very still, because we’re in dense forest. So different from the tundra and the Bering Sea coast where the weather is volatile and changeable. Here, the sky is clear with high clouds–typical weather of the Alaska interior.

The camp is bustling. A few of the younger kids play happily in the dirt while Elders take a break from the bustle near the fire with some chaga tea. A veil of sweet smoke hangs over the camp. They keep the fire pit going with chaga tea and coffee pretty much all the time–and they’re smoking fish and moose meat in the smokehouse. Kids of all ages are running and laughing and working. The setup itself is beautiful, with the tents and the log cabins along the Tanana River. Everything is organized. In the garden, they grow a mix of introduced plants and traditional plants from the area. Most of the activity, though, is down by the water around the fish racks and the beading and art cabins.

The History

The culture camps are intended to strengthen the Tenana culture and ensure that the ways of life continue another 12,000 years. But part of that process is to undo the damages colonialism inflicted.

The discovery of gold in Fairbanks brought gold miners and other settlers to Nenana. In 1903, a trading post was established to serve the locals and river travelers. Two years later, a boarding school, St. Mark’s Episcopal Mission and School, was built just upriver from Nenana, with the purpose of “educat[ing] and train[ing] native boys and girls in the fundamentals of the Christian faith.”

Boarding schools like Saint Mark’s were founded to erase Indigenous culture and assimilate children into Western culture and values. The seemingly innocuous “boarding schools” forcibly removed children from their families to attend what amounted to child re-education camps. In very few cases were these children taught about their own cultures. Instead, most of these schools outlawed everything Indigenous, including languages, ceremonies, and cultural knowledge. This attempt to forcibly assimilate Indigenous cultures through relocation and displacement happened across America, sometimes with children as young as five years old. St. Mark’s Episcopal Mission and School closed down long ago, its buildings eventually swallowed up by the river.

The process wasn’t completely successful, but it was part of a larger movement that contributed to a gap in our understanding of our own cultures. Today, many of the institutions which nurtured and propagated our cultures no longer exist, and we have an entire generation standing at a critical turning point in our development.

The people of this area have a history that predates colonial arrival by millenia, but the boarding schools had a huge impact. Those impacts still reverberate to this day. The culture camps are intended to mitigate the damage and heal from this time period. A culture camp might seem like a minor initiative, but it is an important step. In them, we remind ourselves of our inherent value and that our cultures are valuable, beautiful, and relevant.

The Culture Camp, The Turning Point

Our contact in the community is Eva Dawn Burk who is a Denaakk’e and Lower Tanana Athabascan community leader who volunteers as the lead of the camp. Eva is from Nenana and Manley Hot Springs and serves as vice-chair of Toghotthele Corporation. Her vision for the camp is to create a space for young people to learn, and for the Elder members of the community to pass along their knowledge and values. Eva is also a partner with Calypso Farms and teaches tribal members and youth about agriculture. She is a fierce advocate for food sovereignty. Through programs like the culture camp and her work with Calypso, Eva’s advocacy and love for the community and children is apparent. The camp benefits the whole community, and Eva has plans to expand it.

When we arrive, Eva is not in camp. She is out with the older kids hauling water as the camp has no running water. Eva, we soon learn, is perpetually busy. But even though Eva is not present, we are received warmly. A lot of it has to do with being Indigenous. We are instantly comfortable with everybody and feel the hospitality. They put us to work just like our own families would at home.

When we finally do see Eva, she hops out of a truck and starts directing the kids where the water needs to go, then circles the camp talking to organizers and volunteers. When she is satisfied that everything is attended to, we get introduced to her. But it isn’t long before something else requires her attention and she’s off again. Eva is in charge of the camp but does not run it alone. Her mom, two daughters, many Elders, aunties and uncles, and other volunteers play important roles in making the camp possible. So, we settle in and, taking Eva’s lead, start trying to make ourselves as useful as we can. This proves to be difficult, as the adult volunteers, young adults, and older kids have most everything under control.

The fish racks hold several fish, the skin already cured. These salmon, we learn, didn’t originate from the Nenana River. They were shipped from Bristol Bay, procured by Eva for the culture camp. This year, there is no fishing for Nenana. Across Alaska, salmon runs have been in decline; some primary suspects for this decline are climate change and bycatch, the unintentional catching of species that are not the fishermen’s target species and are often injured or killed in the process.

The fish have thawed enough to be worked on. Adults and Elders take the lead, with many of us eager to engage in the work. Ulus and knives are readied, and we pull fish from the coolers to begin processing them. Kids are naturally curious as we prepare the salmon. The young people are taught how to follow the bones with the blade, using the ulu to slice from the dorsal to the spine, slicing ribs from the filet. A few fish are damaged in the process as young hands engage in unfamiliar work. Fish heads and roe are set aside to eat right away. The entrails and bones are offered to the river or saved for garden fertilizer. Some of the younger kids wander off to participate in other activities, while the older kids, aware of their responsibilities, stay to help clean up the cleaning tables.

As the evening draws near, chairs are folded and areas cleaned. The kids and the families who live nearby go home one by one. Camp volunteers finish packing up and prepping for the following day. A few of us fire up the steam bath. Afterwards, we sit by the river and cool down. It’s a beautiful evening. Clear skies, the height of an Alaska summer. But the night turns cool and damp, and I don’t sleep well, so I’m the first one up. The fire is smoldering. I lay some spruce bark to reignite it. Soon the coals flash into flame, and I put some coffee on. The river is covered in thick fog, but I can feel the warmth of the morning sun through it. The camp is quiet, empty, in total contrast to the life I witnessed yesterday.

An Elder joins me. Charlotte is her name, and she says she’s usually the first one up, laying the spruce bark to revive the fire. We drink coffee and chaga by the fire until people start showing up, revitalizing the camp once again.

The day picks up where the previous one left off, with some folks checking on the fish and others relighting the wood in the smokehouse where salmon and moose are drying. Other people are making fireweed jelly and oils and salves from medicinal plants and berries that the children are taught to identify and harvest. In another cabin, volunteers from Native Movement are making small birch bark canoes and beading chokers and necklaces.

Up-and-Coming Leader, Makiah Gossel

The culture camp is already inspiring a new generation of leaders. This morning, Eva’s oldest daughter, Makiah, is tending the garden. Makiah Gossel is from Nenana and Stevens Village. Her parents are Eva Burke and Ron Gossel. Makiah is one of the young leaders working with her mom to make the camp successful. She is an intern with the Intertribal Agriculture Council and is learning Indigenous plant medicine. She tends the garden multiple times a day. “When I was younger,” Makiah says, “I would help my grandparents with their gardens.” This garden is a recent addition, a mix of wild and domesticated plants.

Makiah is one of many up-and-coming leaders, inspired by and following in the footsteps of their ancestors. She says the camp gives young people a sense of who they are and has been a healing process for the community. She enjoys helping and healing people while on her own journey and has already seen positive impacts on the youth in her community. She wants to continue her education in plant medicine and has dreams of starting a line of hair and skincare products using medicinal plants — as well as opening a salon of her own.

While we’re talking with Makiah, other community members pull up in a boat piled with logs. Volunteers meet them at the shore and haul the logs a short distance where they will be cut. Two young boys are particularly interested in sawing and chopping wood. Under the supervision of adults, the boys help cut the timber into pieces suitable for the fire, steam bath, and smokehouse. The boat leaves and returns not long after with another load, and the process is repeated.

Artist/Elder: Jan

Another volunteer, Jan, is a strong presence at camp, keeping the kids in line. She lives in Nenana, with family from Old Minto and Kotzebue. She was a fluent Dena’ina language speaker before attending school where her language was prohibited and speaking English enforced.

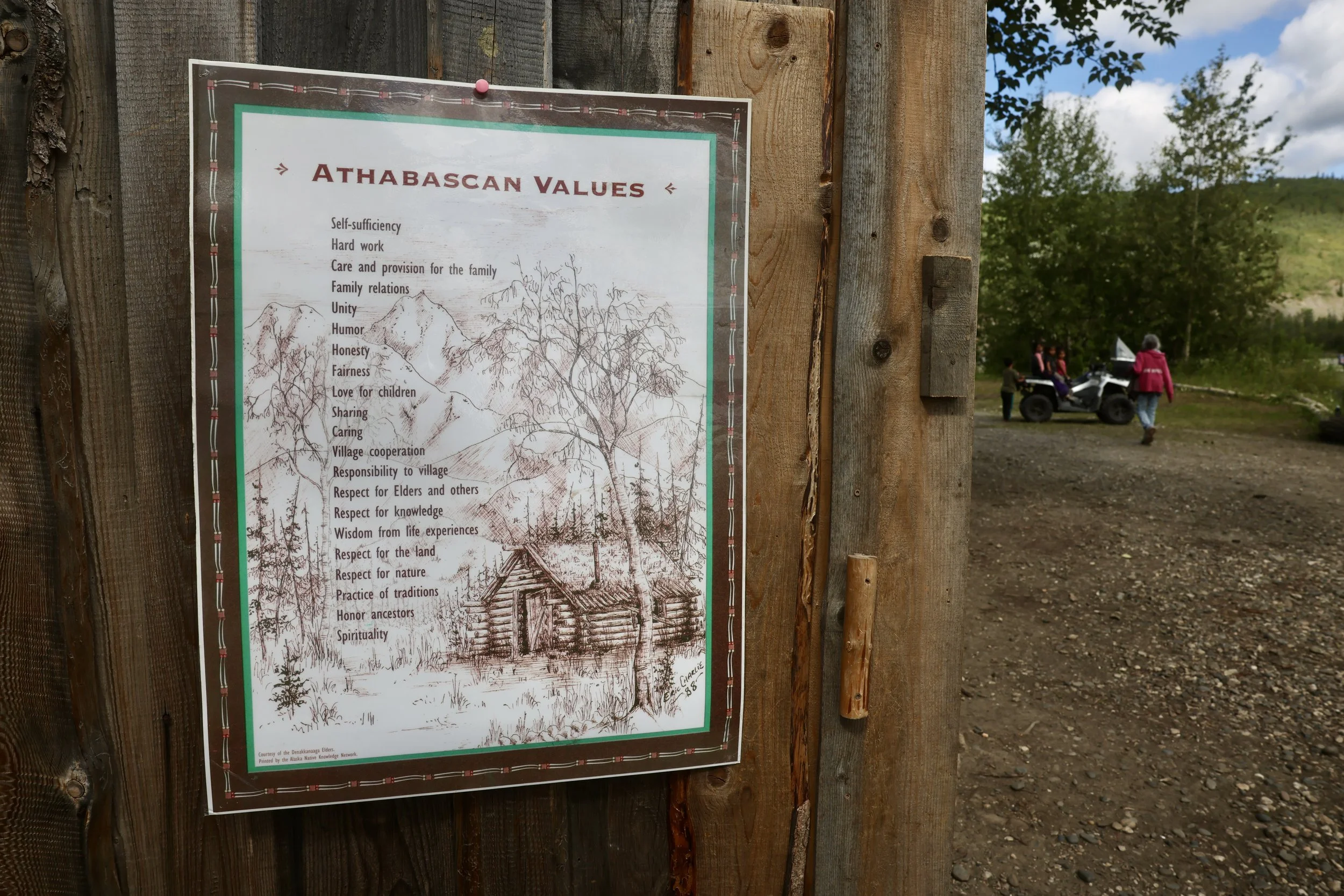

In addition to her other duties at camp, Jan leads beadwork classes. She works to instill the cultural values, and when she has to correct the kids, she reminds them of what those values are. Her people value working hard and being as self-sufficient as possible, and Jan, like many others in the camp, model these values in addition to teaching about them. We leave Jan to her work.

The day winds down, and we begin packing for our journey home tomorrow. We had brought food, but of course they fed us and didn't really need our food so we give the rest to the Elders. After everyone is gone, we fire the steam bath up for the last time. After the steam bath, we sit as before, on the banks of the river and cool off before heading to sleep.

Potlatch

Today, the day of the potlatch, I wake up really early. Charlotte is up, too, starting the fire and getting coffee going. Knowing that other people are going to be waking up soon, I pitch in to get the chairs out and set up. Potlatches are held for a variety of reasons, some, like today’s, to mark important events, others–memorial potlatches– are held to mourn and honor those who have passed. This potlatch will celebrate the end of a successful camp. In Dena’ina culture, how one demonstrates their wealth is by giving it away. The tradition serves several roles. It encourages those who have more than others to share their wealth. It discourages hoarding. It builds community.

One of the Elders is already out driving around town gathering donations of moose meat. She’ll arrive soon and drop it off at camp. When the meat is thawed, the folks will grab their ulus and begin slicing the meat and chopping fat.

I head to the tribal hall to fill water jugs and haul water with Eva’s mom, Joy. Then I pick up a 20-gallon pot and strainer and head back to camp. The massive pot is set on a grate and we add the water, meat, and bones first. Then an entire moose neck is added. The fire is fed, and the men and boys tend to the moose soup. We all take turns stirring. Eventually, the bones are removed and the remaining ingredients are added. Some precooked moose nose is procured, a local delicacy, and moose fat is added to the stew. Camp attendees clean whitefish bones, and fat is whipped with gallons of berries to make Akutaq, a popular dessert in Alaska.

The kids gather up the gifts they made during camp. Prayer is offered and the Elders are served. Afterwards everyone gathers to drum and dance. The young camp goers hand out gifts. Every person in attendance receives something handmade.

The Change

Our way of life has been threatened for a long time. Because the area has been accessible, the people have faced unique challenges. Development is a constant threat. Shortly after we leave, we learn that the Alaska Department of Transportation has proposed the Nenana Tolchaket Road expansion. The 20 miles of proposed new road would open 140,000 acres of traditional use lands for industrial agricultural production.

The concept of nationhood is premised on a shared history, shared vision, and shared values. In short, a nation is premised on a cultural identity. We need to keep our traditions and languages intact, and our lands intact. This important work is done every day in the culture camps. And revitalizing culture gives us a foundation on which to base our true sovereignty.